Now Reading: The Stillness of Time: When a Photograph Was an Act of Endurance

-

01

The Stillness of Time: When a Photograph Was an Act of Endurance

The Stillness of Time: When a Photograph Was an Act of Endurance

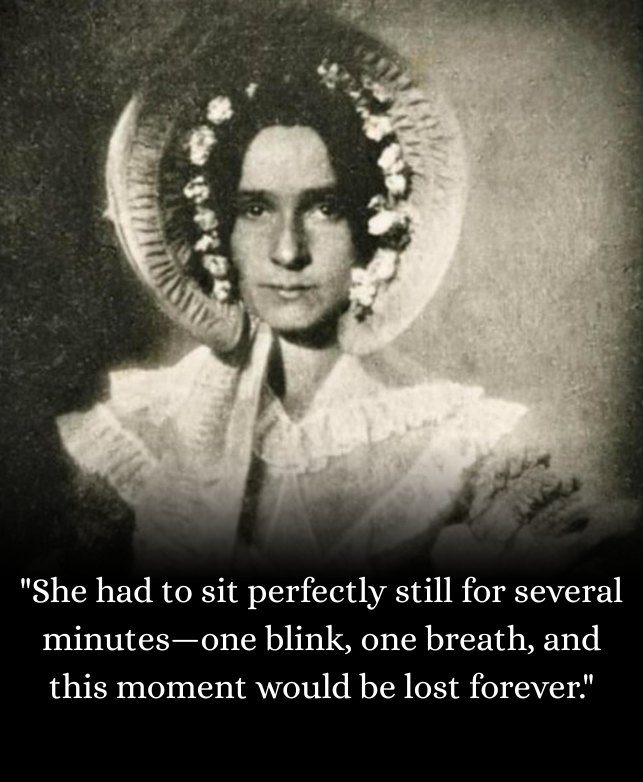

Gazing at old photographs, particularly those from the early days of the medium, one can’t help but be struck by the solemn, often unsmiling expressions of the subjects. We often attribute this to the stoicism of the era, or perhaps simply to the lack of a “say cheese” culture. However, a deeper truth lies in the very nature of early photography itself, a truth beautifully hinted at by the caption accompanying this captivating vintage portrait:

“She had to sit perfectly still for several minutes—one blink, one breath, and this moment would be lost forever.”

This single sentence transports us back to a time when creating an image was not the instantaneous click we know today, but a deliberate, almost meditative act of endurance.

The Dawn of Photography: A Slow Process

In the early to mid-19th century, when photography was in its infancy (think Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, and tintypes), the technology was rudimentary by modern standards. Camera lenses were less efficient, and photographic emulsions were far less sensitive to light. This meant that exposures, the time the lens remained open to capture an image, could last anywhere from several seconds to several minutes.

Imagine sitting for five, ten, or even fifteen minutes, striving for absolute stillness. Every muscle tense, every impulse to shift or scratch an itch suppressed. A blink could register as a ghostly blur across the eyes. A deep breath might cause a subtle but noticeable movement in the chest or shoulders, ruining the sharp focus. Even a tiny tremor could result in a hazy, indistinct portrait.

The Effort Behind the Pose

The women and men who sat for these early portraits weren’t just posing; they were performing an act of physical discipline. Their serious expressions weren’t necessarily a reflection of unhappiness, but often a necessary concentration to maintain perfect immobility. Imagine the strain, the focus required, knowing that the success of capturing this precious, expensive image rested entirely on your stillness.

Special aids were sometimes employed, like head clamps or body braces, to help subjects remain motionless during these long exposures. These tools, while uncomfortable, were essential to achieve the crispness that we now admire in many antique photographs.

A Moment Preserved Through Stillness

This understanding adds a profound layer of appreciation to these historical images. When we look at the woman in this photograph, with her intense gaze and carefully composed posture, we are not just seeing her likeness; we are witnessing the effort, the patience, and the almost sacred commitment required to preserve that moment in time.

In our age of instant selfies and countless digital snapshots, it’s a powerful reminder of how precious and hard-won an image once was. Each early photograph is not just a picture, but a testament to the photographer’s skill and the subject’s extraordinary patience, a captured breath held against the passage of time.