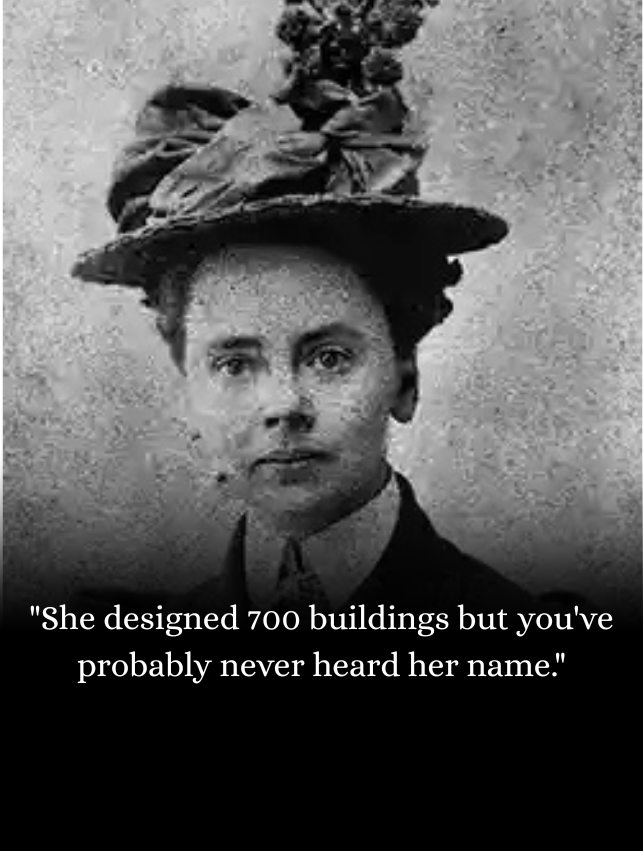

Now Reading: The Architect of 700 Dreams: The Silent Legacy of Julia Morgan

-

01

The Architect of 700 Dreams: The Silent Legacy of Julia Morgan

The Architect of 700 Dreams: The Silent Legacy of Julia Morgan

In 1896, when Julia Morgan applied to the architecture program at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, she was met with derision. Administrators claimed women lacked the mathematical mind and physical stamina for the “man’s profession” of architecture. Morgan didn’t offer a rebuttal; she simply outscored nearly every male applicant on the entrance exam. By 1898, she had become the first woman ever admitted to the prestigious program, setting the stage for a career that would reshape the American landscape.

Engineering the Indestructible

Morgan returned to San Francisco just before the catastrophic 1906 earthquake. While many ornate Victorian structures crumbled, Morgan’s buildings remained standing. She was a pioneer of reinforced concrete, a structural innovation that combined aesthetic beauty with seismic resilience. Her mastery of engineering was so profound that she didn’t just design facades; she built skeletons of steel and concrete that could withstand the volatile California geology.

The Monument of a Lifetime: Hearst Castle

Morgan’s most legendary collaboration was with media tycoon William Randolph Hearst. Over 28 years, she transformed a rugged hilltop into Hearst Castle, a 165-room masterpiece. While Hearst provided the vision of excess, Morgan provided the technical genius. She personally scaled scaffolding in long skirts to inspect craftsmanship, blending Mediterranean Revival styles with cutting-edge structural solutions that defied the engineering limitations of the early 20th century.

A Legacy Beyond the Spotlight

Despite the fame of Hearst Castle, Morgan’s true contribution lay in her 700 other projects. She focused on:

-

Community Spaces: YWCAs, schools, and hospitals designed to serve the public.

-

Empowerment: Her firm was a sanctuary for female draftsmen and engineers who were barred from other offices.

-

Humility: She famously avoided the press, believing that “the profession needs good architects, not women architects or men architects.”

Recognition Long Overdue

Julia Morgan passed away in 1957, and for decades, she was relegated to the footnotes of architectural history. However, as the buildings of her more famous male contemporaries decayed, Morgan’s structures continued to serve their communities, undisturbed by time or tremors. Today, she is recognized not as a “female pioneer,” but as one of the most prolific and technically brilliant architects in American history. She proved that while critics may fade, excellence in steel and stone is permanent.