Now Reading: Beyond the Sagas: The 4,500-Year Human Tapestry of Greenland

-

01

Beyond the Sagas: The 4,500-Year Human Tapestry of Greenland

Beyond the Sagas: The 4,500-Year Human Tapestry of Greenland

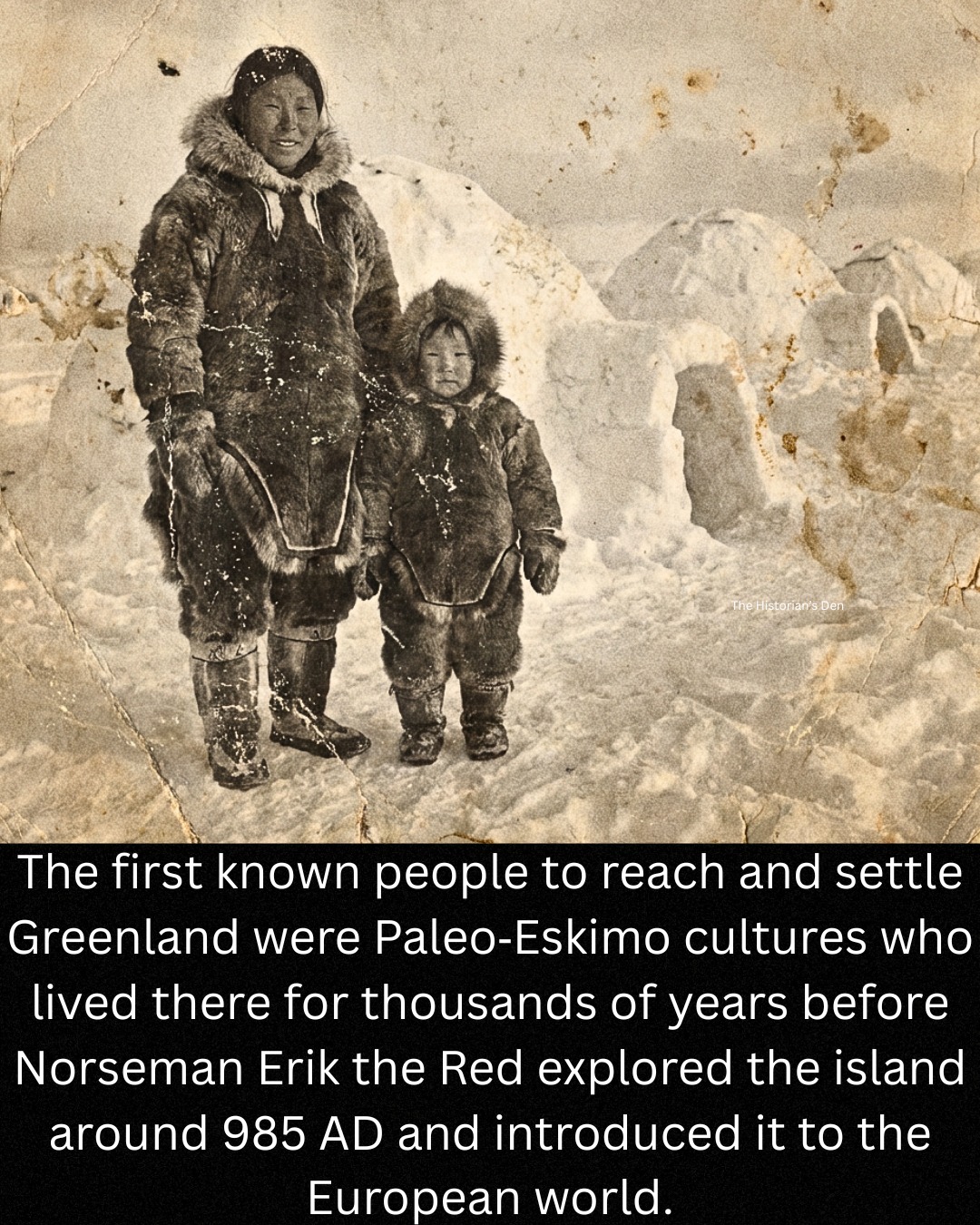

While popular history often begins Greenland’s story with the Viking age, Erik the Red’s arrival in 985 AD was merely a late chapter in a saga that began four millennia earlier. Long before the first Norse longship crested the horizon, Greenland was a landscape defined by Indigenous innovation and a succession of resilient Paleo-Eskimo cultures.

The Pioneers of the Ice

The human chronicle of Greenland began nearly 4,500 years ago. Archaeological sites linked to the Independence I, Saqqaq, and Dorset cultures reveal a sophisticated mastery of the Arctic. These were not primitive wanderers but expert ecologists. Evidence shows they utilized finely crafted microblades, bone tools, and skin-covered watercraft—technologies perfectly adapted to an environment of shifting sea ice and migratory game.

These communities arrived in distinct waves, their movements dictated by the climatic pulses of the Holocene. Through genetic analysis and radiocarbon dating, modern researchers have reconstructed a history of “climatic resilience,” showing how these Paleo-Eskimo groups flourished during warmer phases and adapted as the Arctic cooled.

The Norse Arrival in Context

When Erik the Red led his fleet from Iceland during the Medieval Warm Period, he was entering an inhabited world, not an “empty” frontier. His choice of the name “Greenland”—a clever marketing tactic to attract settlers—belied the harsh reality of the fjords.1 While Icelandic sagas tell of his exile and westward exploration, archaeology at sites like Brattahlíð confirms that Norse settlers coexisted with a dynamic environment and, eventually, the Thule Inuit.

The Thule, ancestors of today’s Greenlandic Inuit, arrived from the Canadian Arctic around the 13th century. Bringing advanced technologies like dog sleds and large skin boats (umiaks), they represented the continuing evolution of Arctic survival.2 In this light, the Norse presence was a brief, marginal experiment in European pastoralism within a land that has always belonged to the deep, enduring traditions of the North.