Now Reading: The Great Miscalculation: Columbus and the Cost of Conviction

-

01

The Great Miscalculation: Columbus and the Cost of Conviction

The Great Miscalculation: Columbus and the Cost of Conviction

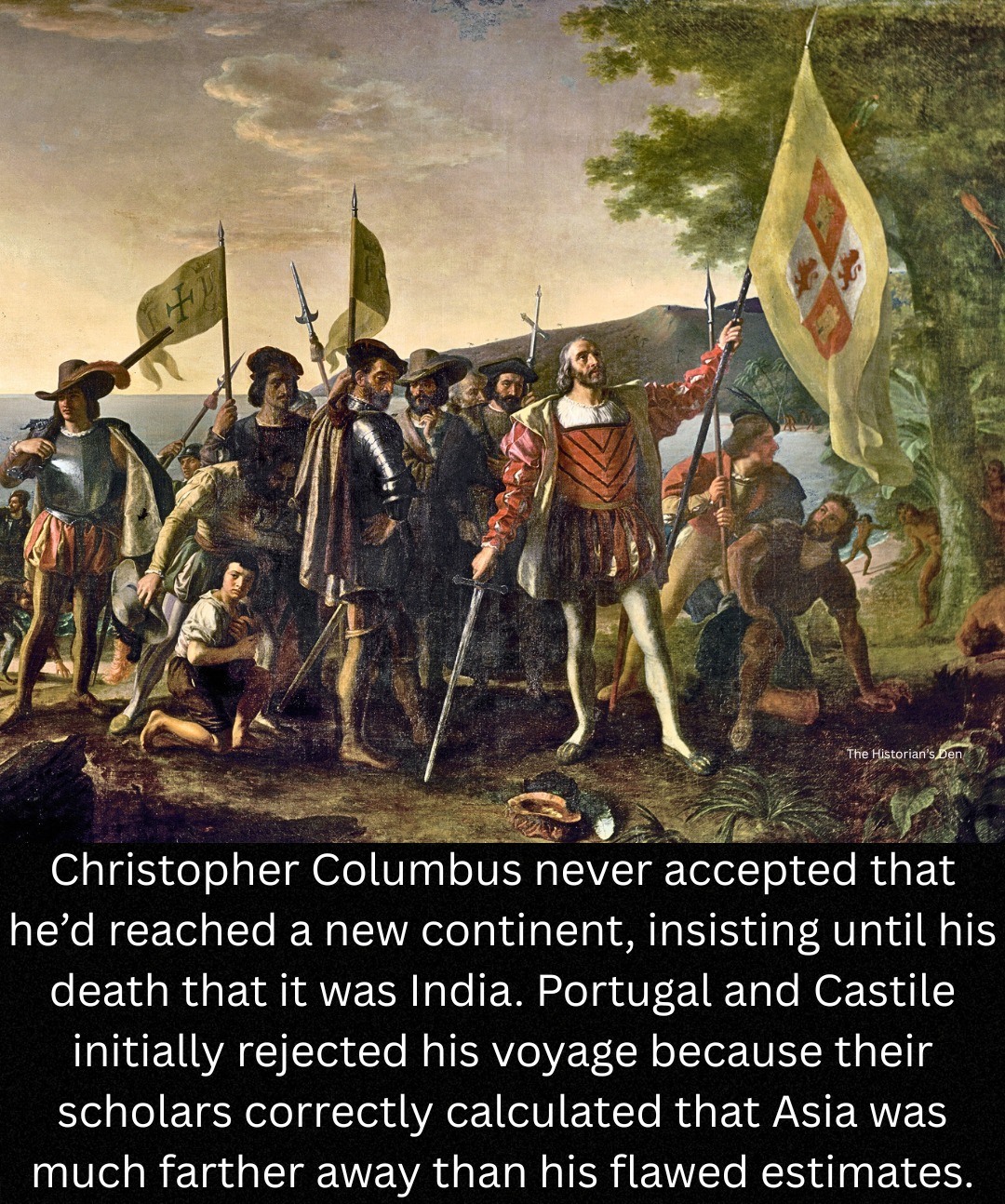

In 1492, Christopher Columbus set sail on a voyage that would change the course of history—not because his calculations were correct, but because his conviction was unshakable. While modern myth often portrays Columbus as a visionary who proved the world was round, his contemporary peers in Portugal and Castile already knew the Earth’s shape. Their issue was his math: Columbus believed the world was significantly smaller than it actually is.

A Gamble Based on Flawed Data

To the navigational experts of the 15th century, Columbus’s proposal to reach Asia by sailing west was a dangerous gamble. Scholars had already accurately calculated the vast distance to the East; they knew a westward voyage would be too long for any ship of the era to survive. His plan was rejected multiple times because the math simply didn’t add up. It was only through the eventual backing of Ferdinand and Isabella that Columbus was able to test his flawed assumptions.

Denial in the Face of Discovery

When Columbus made landfall in the Caribbean, he did not see a “New World.” Instead, he viewed every unfamiliar coastline and plant through the lens of his original bias. He named the indigenous inhabitants “Indians,” firmly convinced he had reached the outskirts of Asia.

Rather than adjusting his theories to fit the reality of the land he encountered, Columbus doubled down. Even as later voyages revealed cultures and landscapes entirely foreign to European descriptions of India or Japan, he refused to reconsider.

The Legacy of Stubbornness

This denial persisted until his death in 1506. While contemporaries like Amerigo Vespucci were already documenting the existence of a separate continent, Columbus remained anchored to his original vision. His legacy is one of profound irony: he opened the door to an era of global expansion, yet he died never fully realizing where he had actually been.